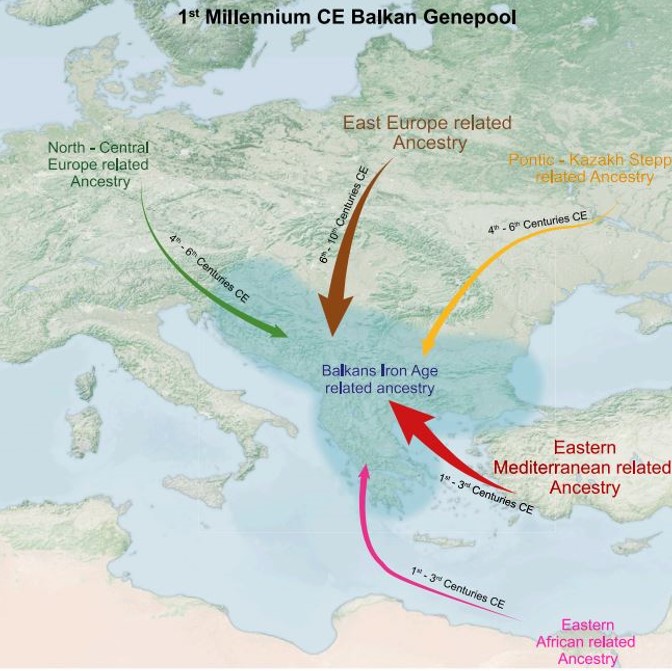

Iñigo Olalde, Ikerbasque and Ramón y Cajal researcher at the University of the Basque Country, has led, together with the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE: CSIC-UPF) and Harvard University, a study in which they have reconstructed for the first time the genomics history of the first millennium of the Balkan Peninsula. To do this, the team has recovered and analyzed the ancient genome of 146 people who inhabited present-day Croatia and Serbia during that period. The work, published in the prestigious journal Cell, reveals the Balkans as a global and cosmopolitan frontier of the Roman Empire and reconstructs the arrival of the Slavic peoples to this region.

For the first time, the team has identified three individuals of African origin who lived in the Balkans under the imperial rule of Rome. On the other hand, the research corroborates that the migration of Slavic people starting in the 6th century represented one of the largest permanent demographic changes in all of Europe, whose cultural influence endures to this day.

The Roman Empire transformed the Balkans into a global region

The Roman Republic first and the Roman Empire later incorporated the Balkans and turned this border region into a crossroads of communications and a melting pot of cultures. This is confirmed by the study, which reveals that the economic vitality of the empire attracted immigrants from distant places to this region.

Through the analysis of ancient DNA, the team has been able to identify that, during Roman rule of the region, there was a large demographic contribution from the Anatolic peninsula (located in present-day Turkey) that left a genetic mark on the Balkan populations. However, no trace of Italic ancestry is observed in the analyzed genomes. “These populations coming from the east were fully integrated into the local society of the Balkans. In Viminacium, for example (one of the main cities of the Romans, located in present-day Serbia), we find an exceptionally rich sarcophagus in which a man of local ancestry and a woman of Anatolic ancestry were buried" comments the first signatory of the article Iñigo Olalde, Ikerbasque researcher from the BIOMICs group of the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) and associated researcher at Harvard University (previously he was a “La Caixa Junior Leader” researcher in the IBE Paleogenomics group).

The team has also revealed the sporadic long-distance mobility of three individuals of African descent to the Balkan Peninsula during its imperial rule. One of them was a teenager whose genetic origin lies in the region of present-day Sudan, outside the limits of the former Empire. “According to the isotopic analysis of the roots of his teeth, in his childhood he had a very different marine diet from that of the rest of the individuals analyzed” comments Carles Lalueza-Fox, principal investigator of the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE) and director of the Museum of Natural Sciences of Barcelona (MCNB).

In addition, he was buried with an oil lamp that represents eagle iconography related to Jupiter, one of the most important gods for the Romans. “The archaeological analysis of his burial reveals that he could have been part of the Roman military forces, so we would be talking about an immigrant who traveled from very far to the Balkans in the 2nd century AD” says Lalueza-Fox. “This shows us a diverse and cosmopolitan Roman Empire, which welcomed populations far beyond the European continent.”

The Roman Empire welcomed barbarian populations long before its fall

The study has identified some individuals of Northern European and steppe ancestry who inhabited the Balkan Peninsula during the 3rd century, during the height of Roman occupation. Anthropological analysis of their skulls reveals that some of them were artificially deformed, a custom typical of some populations of the steppes and the Huns, often called “barbarians.”

These results support historical and archaeological research and show the presence of individuals from outside the borders of the Empire, beyond the Danube, long before the fall of the Western Empire. “The borders of the Empire were much more diffuse than the borders of today's nation states. The Danube served as the geographic limit of the Empire but acted as a communication route and was very permeable to the movement of people,” says Pablo Carrión, IBE researcher and co-first author of the study.

Slavic populations changed the demography of the Balkan region

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, and especially from the 6th century onwards, the study reveals the large-scale arrival in the Balkans of individuals genetically similar to the modern Slavic-speaking populations of Eastern Europe. Their genetic footprint represents between 30% and 60% of the ancestry of today's Balkan peoples, representing one of the largest permanent demographic changes anywhere in Europe during the period of the Great Migrations.

Although the study detects the sporadic arrival of individuals from Eastern Europe in previous periods, it is from the 6th century onwards that a strong wave of migration is observed. “According to our ancient DNA analyses, this arrival of Slavic-speaking populations to the Balkans took place over several generations and involved entire family groups that included men and women” explains Carrión.

The study also identifies that the establishment of Slavic populations in the Balkans was greater in the north, with a genetic contribution of between 50% and 60% in present-day Serbia, and gradually lower towards the south, with between 30% and 40% genetic representation in mainland Greece and up to 20% in the Aegean islands. "Its genetic legacy is visible not only in current Slavic-speaking Balkan populations, but also in other groups that include regions where Slavic languages are not currently spoken, such as Romania and Greece" points out David Reich, a researcher at Harvard University in whose laboratory was carried out the recovery and sequencing of ancient DNA .

Coordination and cooperation to rewrite the history of the Balkans

The war in Yugoslavia in 1991 caused the separation of the Balkan peoples into the different countries that make up the region today, and its consequences persist today. However, researchers from across the region have collaborated on the study. "Croatian and Serbian researchers have been collaborating in the study. This is a great example of cooperation, taking into account the recent history of the Balkan Peninsula. At the same time, this type of work is an example of how objective genomic data can contribute to leave behind social and political problems linked to collective identities that have been based on epic narratives of the past" says Lalueza-Fox.

The team created a new genetic database of the Serbian population, in order to reconstruct the history of the Balkans. "We encountered the situation that there was no genomic database of the current Serbian population. To build it and use it as a comparative reference in this study, we had to look for people who called themselves Serbs based on certain shared cultural traits, even if they lived in other countries like Montenegro or North Macedonia,” says Miodrag Grbic, professor at the University of Western Ontario and visiting professor at the University of La Rioja.

Despite the identity issue, marked by the most recent history of the Balkans, the genomes of the Croats and Serbs analyzed speak of a heritage shared in equal measure between the Slavic populations and the populations of the Mediterranean.

“We believe that the analysis of ancient DNA can contribute, together with archaeological data and historical records, to the reconstruction of the history of the Balkan peoples and the formation of the so-called Slavic peoples of southern Europe” says Lalueza-Fox.

"The picture that emerges is not one of division, but of shared history. The people who inhabited the Balkan region in the Iron Age were similarly affected by migrations during the time of the Roman Empire and later by the later Slavic migrations. Together, these influences resulted in the genetic profile of the modern Balkans, regardless of national borders" Grbic concludes.

Additional information

The study has been led by the Institute of Evolutionary Biology (IBE), a joint center of the Higher Council for Scientific Research (CSIC) and the Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) and by Harvard University, and participated by the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU), the University of Western Ontario and the University of La Rioja (UR).

Bibliograpic reference

Olalde & Carrión et al. A genetic history of the Balkans from Roman frontier to Slavic migrations. Cell. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.10.018

.png)